From Brand Differentiation to Cultural Rebellion

snippet 3 —

Three ways to differentiate your brand. You’ll want to bookmark this.

Quick Recap: What Is Branding?

If brand is “people’s gut feeling about your product or service”, then branding is the act of ensuring that all elements in your ecosystem —marketing & communication, product, public relations, user-experience, even human resources — collaborate towards a positive* gut feeling.

Positioning your business to stand out during the branding process is called differentiation. It is deliberate, thorough and hopefully targetted.

1. Differentiation by Functional Innovation

When you differentiate your brand by functional innovation, you’re promising to address customers’ pain points by developing a new product or feature. At face value, it seems like the only proper way to differentiate.

When the iPhone was first released in 2007, it had revolutionized our understanding of what a smartphone could be, with then-cool infinite touch possibilities. iPhone was Apple’s differentiation by functional innovation within a smartphone market dominated by Blackberry & Nokia.

In 2022, MidJourney made public unfathomable images that generative a.i. spat in a matter of seconds. The novelty of a fulfilling prompt in 2022! That, too, was differentiation by functional innovation in a market saturated with image banks likes Pinterest, Gettyimages, Shutterstock and ShotDeck.

Today, SORA is making us rethink whether we should re-allocate that production budget towards an a.i. video subscription instead. Take a moment to think how OpenAI may successfully differentiate SORA from its rival, Runway.

VERDICT

If you don’t create it, someone else will beat you to it. That is to say, first-mover advantage hinged upon functional innovation is brief and overrated given the pace of (and access to) today’s technology. Everyone catches up with the trend. Market saturation is inevitable.

Significant functional innovation that may warrant brand loyalty gets expensive. Smaller brands can’t survive that race.

Now what?

2. Differentiation by Specialization

Your typical brand owner will want to cast the widest available net to catch as many plausible customers as possible. No one wants to leave money on the table. I, myself, am guilty of that. As I write this, I’m trying to wiggle myself out of being a creative strategy generalist. In a perfect world, I’d like to specialize in brand strategy for B-Corps under 100 employees. I am sure I can narrow this further, but it takes time.

There is an interesting praise to said specialization sung by Blair Enns in his Win Without Pitching Manifesto, and validated prior by Marty Neumeier’s first-hand experience as a package designer in the Silicon Valley back in the mid-1980s. I’ll peel it for ya.

Enns begins his book with “We Will Specialize”.

“If we are not seen as more expert than our competition, then we will be viewed as one in a sea of many, and we will have little power in our relationships with out clients and prospects.

“What the better clients are willing to pay for… is deep expertise. Expertise is the only valid basis for differentiating ourselves from competition.”

Expertise the ten-thousand hours you accumulate in mastering your craft (with or without functional innovation). The more specialized you are in something, the deeper your expertise about it, and the less time you have to avail for anything else.

Eventually, you evolve from a generalist into an expert. Heads will turn because, my friend, with specialization comes confidence that attracts prospects and threatens competition. It gets very primal.

“Nobody attacks an unthreatening generalist.”

Enns compares claiming an expertise to planting a flag in the ground and claiming territory for all to see. That’s exactly what Marty Neumeier recounts in his interview with Chris Do, as he re-enacts a solicitation call to one of his prospect clients in Silicon Valley. He says this to his client:

“(Software package design) is what I own. Nobody else does this. If that’s what you want, we need to meet.”

Neumeier went from a graphic design generalist, to a brand identity designer, to a package designer, to a software package designer. His decision to focus & specialize was fortified by the Valley’s need for an expert who gets their newborn industry. To manifest his specialization, he partnered with clients, tested his package designs, talked with product and sales managers to a point where he practically “indoctrinated them over a few years” with his methods. Eventually, his clients would prescribe him like a medic, “Use this guy!”

That’s the Holy Grail, isn’t it — brand affection to the point of unsolicited word-of-mouth. That’s all a byproduct of Neumeier’s focus on his expertise, and determination to create a differentiated (personal) brand.

Remember, people are willing to pay more for a specialized expert brand they like.

“We're doing the same work as when we were making a profit at ten thousand but now we're charging 60! So you see how that works.”

When you differentiate your brand by specialization, you’re promising to drill down to a granular level of your customer’s pain points, and surgically apply available resources towards a solution.

VERDICT

Specialization is a long-haul and demands a lust for expertise. It will blow false claims made by competition out of the water, but it comes with three caveats:

It doesn’t work as well for a short-term strategy. You first need to accumulate your hours and hone your craft.

It may be matched by other players in the industry; you’re not the only nerd in the classroom.

It may be dissonant with the growth plans of expanding brands. Jordan Rogers points to Lululemon’s expansion from focus on women’s sportswear and yoga pants to engulf men’s apparel, complete with blazers and suits. That is a brand going against the currents of specialization.

3. Differentiation by Cultural Innovation

Reading through Alex M H Smith’s blog, I was first made aware of Cultural Strategy: Using Innovative Ideologies to Build Breakthrough Brands, a must-read by Douglas Holt and Douglas Cameron. In their book, they dissect Nike’s shift in brand differentiation.

“Nike’s famed shoe innovations happened early on and do not coincide with the brand’s takeoff. Nike succeeded with innovative cultural expressions, not with innovative products…

“What Nike did was to view ‘‘performance’’ far more expansively than just how well one can dribble down the court, broadly enough to tap into the anxieties and desires of many Americans who were not competitive athletes.”

Using the word “innovation” here is important, because it implies an act of evolution. As Holt & Cameron put it, Nike’s cultural innovation came against the grain of the cultural orthodoxy of the category prevailing at the times — that is, harnessing the heroic feats of professional athletes. Reading them, Smith argues that cultural innovation is akin to an act of rebellion. He says,

“Brands who pursue (cultural innovation) don’t necessarily need to have any meaningful functional differences with their competitors at all – they simply need to stand for an arresting and motivating cultural position which is deeply at odds with the status quo.

Not until it was braided with cultural influences — and literal collaborations with cultural icons — did the Nike brand resonate with the masses. What we now commonly know as an influencer-led marketing campaign started in earnest right there.

Interestingly, some of these collaboration resulted in sub-brands that combined both functional innovation and cultural innovation:

Nike Air :: Nike x NASA’s Frank Rudy

Air Jordan :: Nike x Michael Jordan

CR7 :: Nike x Cristiano Ronaldo

NikeiD :: Nike x You

Not to mention numerous partnerships with non-athlete cultural influencers to produce pivotal campaigns and / or special editions of existing products, like Virgil Abloh; Travis Scott; Drake and Kendrick Lamar to name a few.

Today, Nike — who invented cultural innovation as a means to branding — has made it so mainstream that it is borderline cultural clichés. It is hard to see the merit of it all until we look back at where it all started. According to Holt & Cameron, in 1981 — ten years after launch — Nike’s sales had reached $458 million a year. Today, Nike’s market capitalization stands at $142.25 billion. That’s a growth of 310x during my lifetime.

Nike still manages to rejuvenate its commitment of being “at odds with the status quo”. Its endorsement of Colin Kaepernick in 2018 marked a brilliant understanding of cultural opportunism. For better or worse, the brand stood out in a favorable light, and amplified Kaepernick’s stance against social injustice and Trump’s America.

In a remarkable interview with Chris Do, Seth Godin articulates how radical innovation (functional be it or cultural) eventually has to subside into something more colloquial, easily digestible by the mainstream.

“If we look at a company like Apple, for 25 years it was a company where their customers were nerds, early adopters and edge cases. And since Steve has died Tim (Cook) has chosen to change the company to one that almost never innovates in a significant way but instead offers a different kind of upside to a different kind of user.

And so, as I am shifting more and more to being a teacher my goal is not to say something so revolutionary that no one ever thought of it before; my goal is to talk about things that are important that people can understand in ways they haven't understood before.”

Cultural differentiation takes balls. Remember these?

My guide here is to ask, “Was this campaign against the cultural orthodoxy of the category?” Highlighting my faves below. Which one is yours?

Cadbury Gorilla 2007 — differentiation by emotive juxtaposition

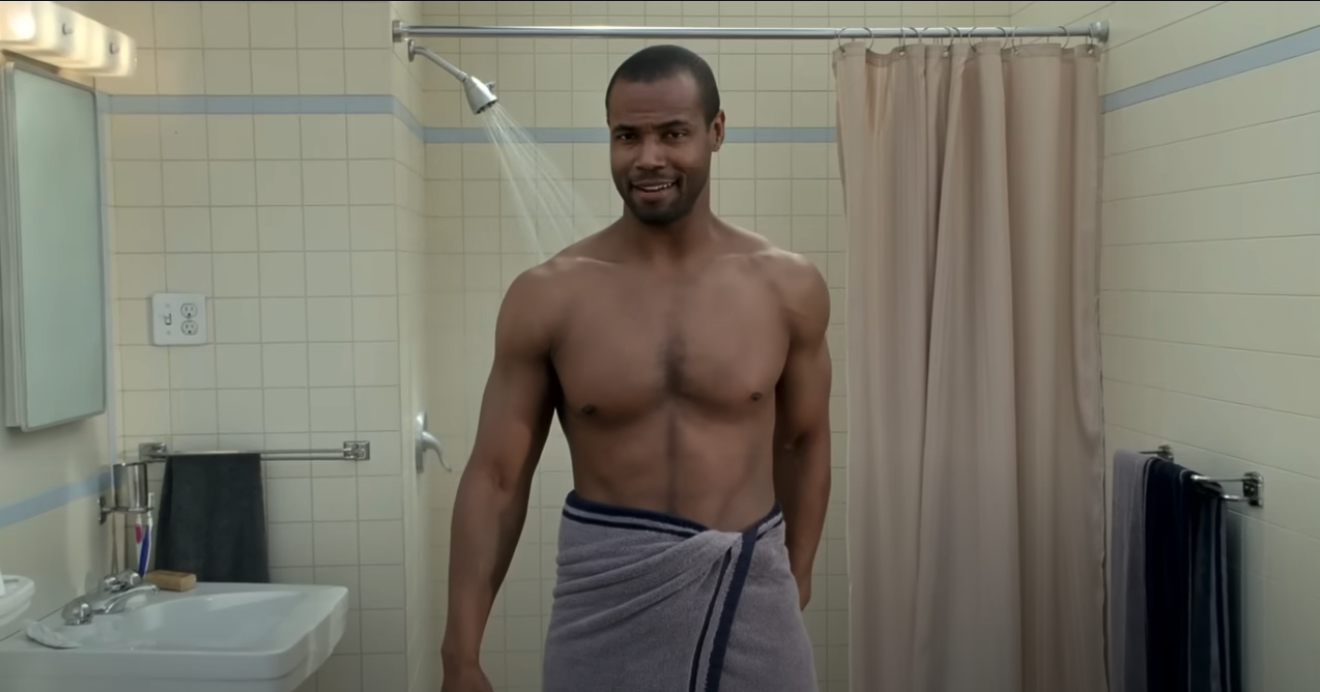

Old Spice Hello Ladies 2010 — differentiation by slapstick humor

Diesel Be Stupid 2010 — differentiation by association with the contrary

Skittles Touch The Screen 2012 — differentiation by slapstick humor & reformatting

Dollar Shave Club Launch 2012 — differentiation by slapstick humor

Lurpak Adventure Awaits 2015 — differentiation by shock juxtaposition

Nike Sacrifice 2018 — differentiation by association with the contrary

Headspace Netflix Series 2021 — differentiation through a new format

Liquid Death Big Game 2022 — differentiation by shock juxtaposition

When you differentiate your brand by cultural innovation, you’re acknowledging your customers’ pain points by poking their sense of identity (which tribe do I belong to?). You give them a symbol to hold on to against the mainstream, rather than a functional solution.

VERDICT

Cultural Innovation comes across as the easiest of all three approaches. Perhaps? Still, it demands thorough knowledge of the subculture you’re communicating with. It demands the insight of a keen journalist, the wit of a talented improv comedian and the eloquence of a verbose orator.

It takes an artist like Picasso, who knows the rules of the Atelier really well, but in time breaks them in defiance of the status quo.

Footnote :: Positive brand sentiment can be better understood in light of Kevin Roberts’ brand love pyramid. In his book "Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands,” the former CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi introduces Brand Love in a hierarchy: Respect > Trust > Affection > Loyalty > Commitment.